The responsibility of Environmental Educators, challenges and opportunities for the promotion of an ethics of responsibility

Article published in the proceedings of the 7th World Environmental Education Congress (WEEC, Marrakech, 9-14 June 2013

Yolanda ZIAKA, June 2013

The value of responsibility is an question at the core of Environmental Education. How do Environmental Education actors perceive and assume their *own* responsibilities when facing ethics, governance and development-model issues? Is Environmental Education the “teaching of predefined choices” or an “education to choices”? Every answer to this question constitutes a political choice and determines how the educator will orient his or her action. Our research, based on the analysis of a variety of educational actions at the international level, reveals a divergence of conceptions related to the conflicting nature of the relationship between the environment and development and to economic and political stakes, which often condition the action of educational actors. This analysis begs reflection on the very meaning of the concept of responsibility and on the meaning of our mission as educators.

Are we running into an abyss?

Our globalized world is obviously undergoing a deep crisis; it is an economic, ecological and social crisis, a systemic crisis.

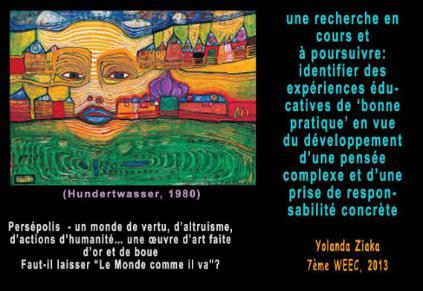

What are the features of this crisis? In Voltaire’s philosophical tale published in 1748, “The World As It Goes”, a reflection of Voltaire’s society in his era, we find – as if nothing had changed since then – a fine and extremely perspicacious analysis, it would seem, of our own era.

In this tale, the genii presiding over the empires of the earth are angry about the Persians’ excessive behaviour. The angel Ithuriel, one of the genii, entrusts the Scythian Babouc with a mission. Babouc is to go to Persepolis and examine its inhabitants, accused of every evil, then to give Ithuriel a faithful account, based on which Ithuriel would determine whether to punish or exterminate the city. On arrival in Persepolis, Babouc observes the behaviour of the city’s inhabitants and discovers a world governed by violence, injustice, vice, crime… Babouc, torn between the city’s violence and a few expressions of virtue among its inhabitants, is surprised: « ’Unaccountable mortals! as ye are,’ cried he, ‘how can you thus unite so much baseness and so much grandeur, so many virtues and so many vices?’ » Should this world be destroyed?

Will we be punished for our crimes, like the inhabitants of Persepolis? Are we standing today at the point of advancing towards our destruction?

The originality of today’s crisis lies in the fact that an entire civilization seems ready to collapse, based on its conquest and domestication of nature for an economic growth seen as infinite. Doom-saying voices are rising everywhere. The melting of continental glaciers, the rising levels of the sea, the hurricanes, infectious pandemics… Edgar Morin declared in 2013: “Everything indicates that we are running into an abyss and that we need, if possible and if there is still time, to change our path.” (Morin, 2013).

Intellectuals who have influenced contemporary thought stress the urgent need for a new conceptual paradigm, for a culture of responsibility (H. Jonas, 1979), for planetary citizenship (M. Serres, 2009), for an education system that supports the development of complex thought (Morin, 2011).

If it is true that “all the crises of planetary humankind are at the same time cognitive crises calling our knowledge system into question” (Morin, 2011), then we have a crucial mission of education to face the crisis, be it called Environmental Education (EE), Environmental Education for Sustainable Development (EESD), Education for Sustainable Development, Education for a Viable Future, or by any other name. The question of our own responsibility as educators thus becomes crucial.

We wished to explore the question of responsibility of the actors of Environmental Education through a survey based on interviews of educators from 10 countries in all the continents, and on an analysis of their writings and research reports at the international level.

The challenges of a culture of responsibility

The educator’s great dilemma, as we see it, is as follows: Is Environmental Education the “teaching of predefined choices” or an “education to choices”? Or, as the question was raised by one of our interviewees: “What will we discuss with our students: Where will we put the waste-sorting dustbin? Or, what are the main lines of the current development model and what are its consequences?” Answering this question constitutes a political choice and determines the orientation of every educator’s action.

In the light of our analysis, it appears that our responsibility as educators consists in:

-

educating to autonomy and critical thought; questioning the form of development and the form of governance: “the rules for managing the Common House at a time when the Common House has become the planet”;

-

questioning “politically correct” concepts (such as sustainable development), exploring the potential of alternative social projects (“degrowth”? “ecodevelopment”? “the œconomy”? etc.);

-

teaching how to live together, contributing to building respect among humans and between humans and the environment;

-

contributing to raising awareness of the intrinsic value of nature, independently of how we use, consume and exploit it;

-

educate citizens to trust in the value of citizen action, fuel their desire to act, make them able to assume their responsibilities, therefore to act at every level, from the local to the global;

-

becoming involved in and encouraging collective concrete action at the local level and taking concrete responsibility by recognizing the educational value of the whole of the local population’s participating in the public debate.

Let us return to Voltaire’s tale and how it continues. The angel’s envoy, Babouc, discovers in Persepolis, alongside vice and crime, a world of virtue, altruism, generosity, actions of humanity… Fearing that Persepolis would be condemned, “[h]e caused a little statue, composed of different metals, of earth, and stones, the most precious and the most vile, to be cast by one of the best founders in the city, and carried it to Ithuriel. ‘Wilt thou break’, said he, ‘this pretty statue, because it is not wholly composed of gold and diamonds?’”. Ithuriel resolved to think no more of punishing Persepolis, and instead to “leave ‘The world as it goes’. ‘For’, said he, ‘if all is not well, all is passable.’”

Should we leave “the world as it goes”?

Voltaire is not a moralist. According to him, evil is part of man, but man and society are perfectible. It is best to deal with this fact and work usefully rather than destroy everything.

We can only bank on the nobility of the human soul, on virtue. Edgar Morin declared: “I am increasingly convinced that a reform of knowledge and thought, hence of education, is vital to allow humankind to find and take the new path” (Morin, 2013). Our mission as educators would be to seek “the new path”, to explore this new conceptual paradigm, to try to get an ethics of responsibility acquired.

An ethics described in a very beautiful and colourful way by Albert Einstein:

“A human being is a part of the whole called by us universe, a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feeling as something separated from the rest, a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be . . . to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.”

An enormous task for educators. Mission impossible? Edgar Morin reminds us that the first educational truth formulated by Plato was that “to teach, you need Eros.”

Read the full text… (original text in French)

Downloads: yziaka-7weec.pdf (340 KiB)